A Silver and Black Intervention

- Dominic Mucciacito

- Sep 7, 2024

- 6 min read

Updated: Sep 17, 2024

"It sounds like a cliché, I know. But when you've been very ill, the good things look different."

-Rolf Benirschke

One afternoon after a soccer practice at La Jolla High School some of the football players coaxed a first generation American kid named Rolf Benirschke into trying some field goal attempts. The 5'11" 140 pound soccer player hit a few with ease, so the kids moved him back to try one from 50 yards.

On the first attempt he split the uprights.

The La Jolla football coach was watching the impromptu tryout and offered Benirschke an opportunity to play football. Envisioning spending his senior year as a tackling dummy held zero appeal to Benirschke initially, but he made 12-14 field goals that season, was named a San Diego Union Prep Athlete of the Week after making a 45-yarder, and was recruited by a number of schools—including Don Coryell's San Diego State Aztecs.

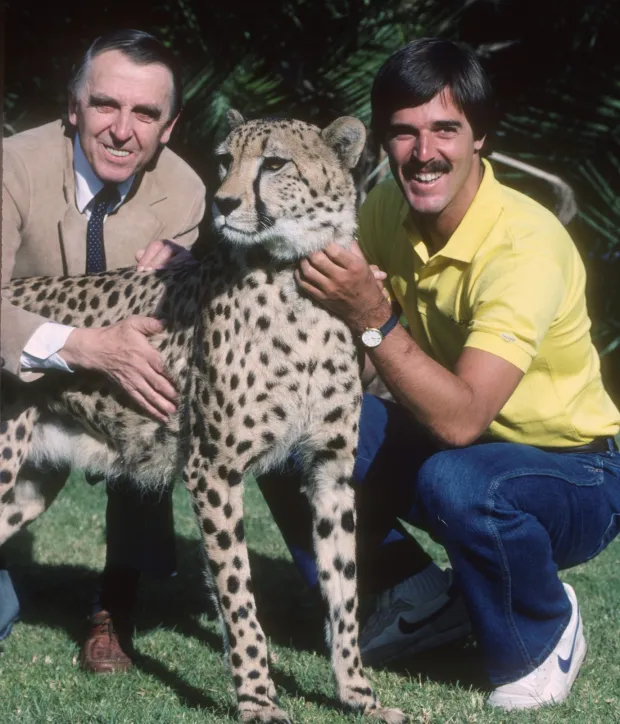

But Benirschke was through with football, or so he thought. His interest laid elsewhere; they laid under trees for the shade and camouflage! He wanted to pursue a zoology degree at UC Davis and devote himself entirely to his love for animals.

This time another coach talked Benirschke into kicking when he learned that he was already enrolled. It took more convincing this time and the staff worked out an arrangement where Benirschke could split time between his placekicker duties and the soccer team.

By the time he graduated with his zoology degree in 1977 he needed to make another decision: go to graduate school or report to an NFL training camp. Though technically Benirschke was not Mister Irrelevant, he barely missed out being selected 334th out of 335 in that year's draft.

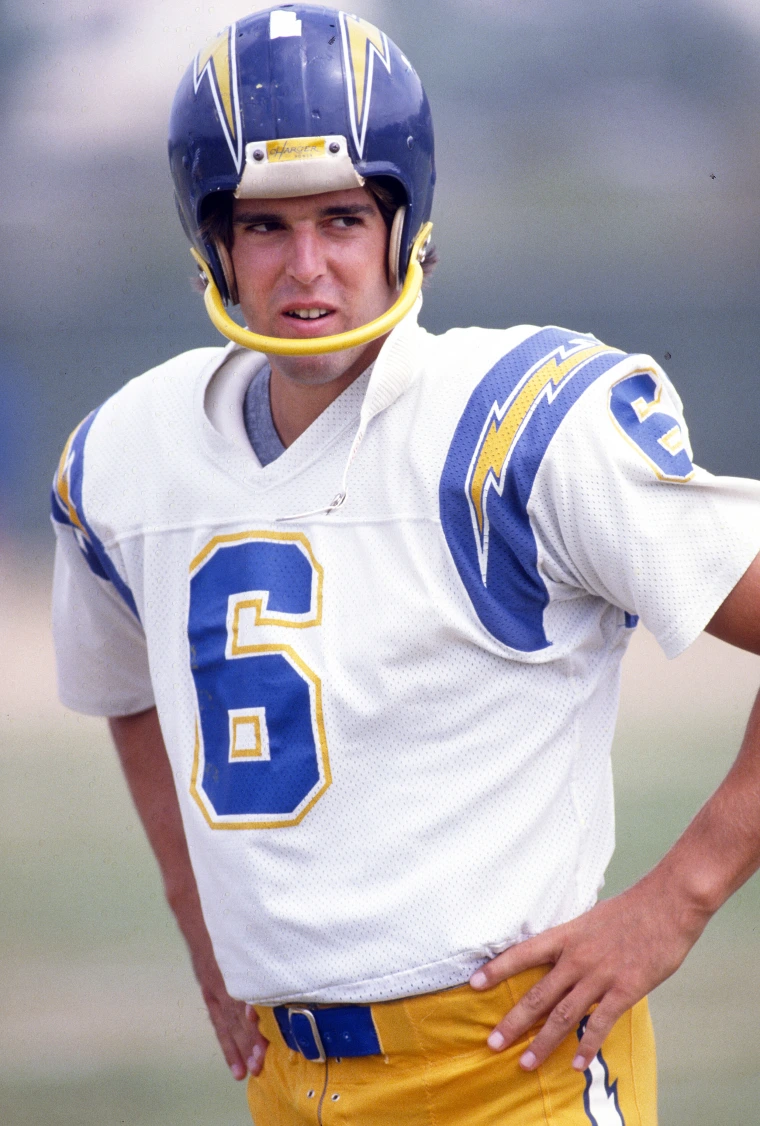

After being claimed off waivers by the Chargers, Benirschke drove home. When he showed up at the team's offices holding his equipment in a box a receptionist asked, "Young man, who is the delivery for?"

Though the Chargers special teams were decidedly not special, the rookie won the job kicking for his hometown San Diego Chargers. The team about to come out of a decade-long rebuild and Rolf became a key contributor to one of the greatest era's in team history.

One dream coming to fruition is something, but two? A year later Coryell also returned home and became the Chargers coach after an acrimonious ending in Saint Louis.

But even fairy tales have to include pitfalls and adversity.

During the 1978 season Benirschke started feeling sick. He thought it was food poisoning but had never heard of a case that lasted for weeks. He struggled to maintain both his appetite and his weight. Doctors discovered that he suffered from Crohn's disease, but knowledge and treatment for the condition was still in its infancy. Benirschke would get worse before he got better. Much worse.

Kickers are all creatures of habit. They crave routines.

Benirschke's routine started in his hospital bed, once unplugged from his I.V. he dressed and kicked for a pro football team and then return to the hospital to ensue his treatment.

The game lionizes sacrifice and toughness so Benirschke soldiered through despite the pain. Between the vomiting, the diarrhea and the cramping the second-year kicker gutted it out; leading the team in scoring and converting 82% of his field goal attempts.

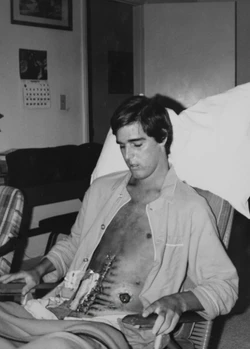

But his body was withering. (Take a look at how gaunt Benirschke is on the sidelines by week 2 against the Oakland Raiders in 1979 in this screengrab from the second quarter.)

A few minutes later with the Chargers leading the Raiders 14-3, linebacker Woodrow Lowe intercepted Ken Stabler's pass over the middle and returned it for a touchdown. Benirschke came on to attempt the extra point.

As the ball sailed through the uprights Raiders cornerback Lester Hayes hit Benirschke, blindsiding him with a forearm shot into his ribs. There are cheap shots, and there is hitting an emaciated Crohn's patient surviving on meal-replacement shakes and an I.V. drip—after the play is over.

Hayes cracked three of his ribs with the late hit. A penalty was thrown, followed by a few retaliatory punches. (The Chargers won 30-10.) Benirschke's chest was wrapped and iced, but the agony would only intensify.

The Raider brand has no geographic nucleus. Maybe the whole pirates marauding at sea pillaging as they go shtick has licensed this nomadic existence from devotees jumping ship. As a brand, the image of the one eyed pirate is more popular today than ever. The team of castoffs, miscreants, and pariahs still holds the same pugnacious appeal it did in the days of Alzado, Matuszak, and The Assassin, Jack Tatum.

How else can you explain roughing up a 150-pound kicker literally on death's door?

The inner bad boy in every twelve-year-old bully—who began bullying out of the fear of being bullied themselves—finds strength in the monochromatic silver and black. They make t-shirts in affirmation of their masculinity. Real Men Wear Black.

Benirschke was at the end of his rope and relented to the doctor's orders. He would not be checking out of the hospital to kick for the Chargers until his health improved.

He had been fighting so hard to keep his job; to not let his teammates down; to not let Coryell, who had made every concession possible to allow him to play, down too. But he was fighting the wrong battle, and losing ground on a more important front.

Doctors decided to remove the diseased part of his intestines but worried that Benirschke was so frail that he might not survive the procedure. Surgery was delayed for a few weeks in the hope that a central I.V. line (TPN) inserted in his jugular administering dextrose, fats, aminos, and minerals could buttress the numbers on his medical chart.

A surgery removed ten inches of his large intestine. A week removed from the initial surgery a bacterial infection continued to show in his bloodwork. Doctors told Benirschke that they would need to open him up again to find what was wrong. Sepsis would kill him if the hospital's antibiotics continued their feeble amelioration. He was crestfallen.

When the surgeons opened his gut up again they found that the suture they had made between the colon and the ileum was leaking. No wonder the last week had been another marathon of agony. The Chargers kicker was lucky to be alive.

"I'm dying Dad. I know it. You know it. They all know it."

At his lowest, Benirschke asked his father, who was also a pathologist who worked at the hospital, to promise that when the time came he would not let them keep him alive with machines if hope was lost.

It never came to that.

After narrowly avoiding a third surgery Benirschke's numbers finally started to improve. With his navel stitched together with piano wire to reinforce the sutures and an ostomy bag now affixed to his waist his next opponent was to tackle solid food again. He was discharged on November 2, 1979. He weighed 123 pounds.

Football seemed as far away as the goalposts from the tailgate barbecue.

A few weeks later, and a few pounds heavier (130 lbs.), Benirschke was invited by the team to watch their home game against the defending Super Bowl champions, the Pittsburgh Steelers.

When he dropped in on the Chargers locker room before the game to say hello equipment manager Sid Brooks presented him with a game jersey. Defensive tackle Louie Kelcher proposed to Coryell that Benirschke be one of the team's captains that day.

"I don't know if I can walk that far," said Benirschke, who knew that team captains had to go to midfield for the coin toss.

"Don't worry Rolf. If you can't walk all the way I'll carry you," said Kelcher.

The Steelers would win the Super Bowl again in January, but on that November afternoon, wondering if they would ever see their kicker alive again, the Chargers could have beaten the Monstars in Space Jam. The final score: Chargers 35 Steelers 7.

The following season Benirschke was back in lighting bolts. The team didn't ask him to tackle on a kickoff as he was, and remains, the only player to ever play in the NFL after ostomy surgery. He kicked for the Chargers for seven more years and is still the 4th highest scorer in team history.

His inspirational story resulted in more than just standing ovations in San Diego; during his career he won NFL Man of the Year, The Breibart Award, Comeback Player of the Year, NFL Players Association Hero of the Year, Philadelphia Sports Writers Association Most Courageous Athlete, and was selected to play in the Pro Bowl. In 1997 Benirschke became the twentieth player to be inducted into the San Diego Chargers Hall of Fame, and was named to the Chargers’ All-Time team.

So, in a weird way, you could say that Lester Hayes’ cheap shot was the intervention that helped save Benirschke's life.

You could say that the pain of his broken ribs forced the ailing kicker to face up to some hard truths and seek treatment.

Ain't life funny like that?

Sometimes what happens in Vegas doesn't stay in Vegas. Sometimes it follows you home and forces you to clean house.

Sometimes providence sets you down so low that you wish you could die. Sometimes providence wears an eye patch and tells you that you can go fuck yourself. Sometime providence drops 63 points on you.

My point is, you don't know it at the time, but sometimes that car crash actually did you a favor.

Comments